Drawing inspiration from the strangest places

The never-ending quest to improve

I peak doing cardio deep in the summertime. It is a predictable phenomenon; as predictable as in the deep winter I peak insofar as size and strength. I think it only logical and natural to sync up seasonally appropriate training with seasonally appropriate nutrition to optimize results. Ergo, thick, homemade stews, luscious roasts, nutrient-dense eating is paired up with high-intensity power training. Cardio is done but without the gusto reserved for summer. The cold weather, gourmet peasant food eating and hardcore weight training is optimal for maximizing muscle and power.

With the end of winter comes springtime, a transitory season. Naturally the foods lighten and the weight training lightens and the cardio (preferably done outdoors) increases. Summer arrives and what better time to lean out than in the hot days of July and August? Eat like a bird, clean and light, engage in massive amounts of varied cardio. Weight training is light and precise. Come fall, another transitory season, time to head back in the other physiological direction. Syncing seasonally appropriate eating with seasonally appropriate training keeps the transformational process alive, vibrant and in tune with deep primal rhythms.

My summer cardio so far has been superb. I have rediscovered sprinting. I had lost the ability to sprint unbeknownst to me, through disuse. Use it or lose it. I hadn’t sprinted in 20-years and got called on to do so and I stood frozen, like the tinman before oiling. I was shocked. Upon reflection it was easy to predict: why would I assume that I would retain the ability to run balls-out without having done it in decades?

The breakthrough came when I taught myself how to sprint without injuring myself. I found a way to go all out, repeatedly yet safely, without injury. I’d attempted “sprint comebacks” in previous years and by the third sprint session I would severely pull a hamstring ending that year’s sprint experiment.

I hit on the idea of making sprinting analogous to working through the gears on a manual transmission in a car. I began sprinting using three gears: 1st, 2nd and 3rd gear. It was a ramp-up strategy, one that allowed me to go 100% all out but without ripping hamstrings and derailing the effort. I could participate long-term, in the sprint game if I followed the “three-speed” protocol. The procedure was simple and was used on all sprints, regardless the length of the sprint. Most of my sprints were 30-60 yards with the majority being 50-yard bursts.

I attain yet not exceed 75% of my all-out capacity for the first half of any sprint. This purposefully restrained start allowed me to concentrate on establishing perfect technique. Halfway through the sprint, I would hit second gear and take it up to 90%. Then, for the final 25% of any sprint, mash the accelerator, generate 100% all out maximum effort, this while maintaining the perfect run technique established during the first 2/3rd of the sprint.

I was quick to discover that my sprint style was pathetic. I had adopted a sort of “carry-hands” style where I used my legs to carry my non-pumping arms. My guns were passengers or cargo. I noted how the top sprinters (as seen on TV) powered their sprints with a violent arm pump. I started “leading with the arms” and it was a revelation: the arms can “turnover” faster than legs and fast arm turnover forces the legs to follow quicker than they could or would on their own. Wow.

I made fast progress continually reminding myself in real time to lead with the arms, to lean forward and to relax my tight-ass hamstrings and sink and dig. Attempt to extend the stride and eat up the ground in front of you as fast as possible.

My most recent revelation, insofar as cardio/sprinting involved aspiration.

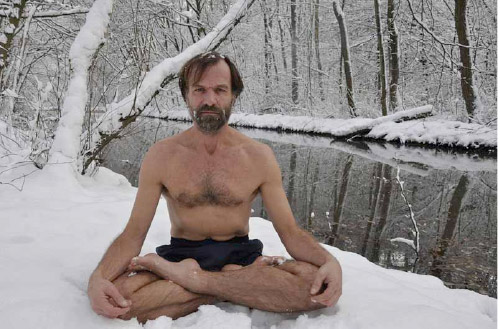

Inspiration can come from weird places. Six months ago, I had been asked to write the forward to Wim “The Iceman” Hoff’s book. Wim was creating a firestorm with his use of highly sophisticated breathing techniques to seize conscious control of the immune system. It made him not only impervious to cold; as it turns out cold resistance training creates a multitude of other physiological and psychological benefits.

I saw a video of Wim teaching a class how to breath. It put me in mind of a Kundalini yoga practice we did back in the early 1970s, “the breath of fire.” Technically, the breath training taught by kundalini yoga instructors bore many more similarities than dissimilarities to Wim’s highly specific breathing techniques. It rekindled an interest in breathing techniques. I wondered if it could somehow be expropriated to improve sprinting? Kundalini breath techniques to improve speed or distance? That seemed a bit of a stretch.

More unlikely inspiration came from rereading Paul Frere’s 250-page book, The Racing Porches, a Technical Triumph. In this incredibly complex and complicated book, Frere, an engineer and racecar driver follows the technical evolution of racing Porches over a ten-year period. In a nutshell, Porsche made their bones in racing by building super-light, super aerodynamic cars. We follow the evolution of a puny 183 cubic inch engine: using carburetors, the engine can produce 250 horsepower.

Carburetion provides a fuel/air mixture that is sucked into an internal combustion engine on the downstroke. Porsche switched from carbs to fuel injection and eventually could produce an awesome 420 horsepower out of the tiny engine. Fuel injection, as the name implies, injects the fuel/air mixture, forcing combustible mixture into the cylinders created a massive horsepower bump. In the early 1970s Porsche led the world in turbocharging.

The turbocharger forced air into the cylinders far more than even fuel injection. The only thing better than a turbocharger was twin turbochargers. Porsche could generate a mind-blowing 600 horsepower out of a twin turbocharged 3 liter. For Can Am racing Porsche created a twin-turbo 5-liter 305 cubic inch engine that generated 950 horsepower! Holy hell, this in a 1700-pound car.

Thoughts about Wim’s breathing and the Kundalini “breath of fire” combined with the realization of the radical increase Porsche engineers obtained by forcing the breathing. How does all this convert to sprinting?

I discovered that when I jogged, ran or sprinted, I was not using my full lung capacity. I could run all out partially breathing. I was not maximally expanding my lungs. Most people don’t. It takes concentrated effort to fully fill the lungs. To fill that empty top third of my lungs with extra air, I needed to turbocharge and force that extra air into the lungs. Unless it made me dizzy and topple over from hyperventilation. It needed some testing.

I experimented with my turbo-breathing in my next sprint session. I concentrated all my attention on the end of each breath. At the point where I would normally begin exhaling I now lifted my shoulders, opened the front of my chest and forcibly took in extra air. I made a conscious effort to “over-breath” on every breath while sprinting. Normally, when I would sprint, I would let my breathing take care of itself with no real thought or attention paid to breathing.

When I began using this forced induction strategy, I was worried that I might create some sort of hyperventilating effect, make myself lightheaded and keel over. That was not the case. In fact, I discovered that by turbocharging my lungs I could go all out for further distances. While my sprints are not faster I am able to effortlessly keep up the 100% all out sprint for far longer distances before I “tie up” and am forced to quit.

This is exciting. All my sprint lengths have doubled. My cardio circuit consists of mountainside trails on a farm. On the flat sections running balls out 100% and using turbo breathing I can go twice as far before gassing out. Not a hint of hyperventilation or dizziness. On the contrary, it feels as if I have upped my oxygen intake by a considerable lot and, further, longer sprints going all out will, over time have a profoundly beneficial effect on my cardio capacity and the health and functionality of my internal plumbing.

Faster arm movement, longer stride, turbocharged breathing and lots and lots of sweat-drenched, lung-searing, pedal to the metal sprinting sessions – arguably the greatest of all cardio modes.

About the Author

As an athlete Marty Gallagher is a national and world champion in Olympic lifting and powerlifting. He was a world champion team coach in 1991 and coached Black's Gym to five national team titles. He's also coached some of the strongest men on the planet including Kirk Karwoski when he completed his world record 1,003 lb. squat. Today he teaches the US Secret Service and Tier 1 Spec Ops on how to maximize their strength in minimal time. As a writer since 1978 he’s written for Powerlifting USA, Milo, Flex Magazine, Muscle & Fitness, Prime Fitness, Washington Post, Dragon Door and now IRON COMPANY. He’s also the author of numerous books including Purposeful Primitive, Strong Medicine, Ed Coan’s book “Coan, The Man, the Myth, the Method" and numerous others. Read the Marty Gallagher biography here.