Putting yourself on the SPOT with periodic formal competition.

Want to take yourself and your physique to the next level? Consider formal competition.

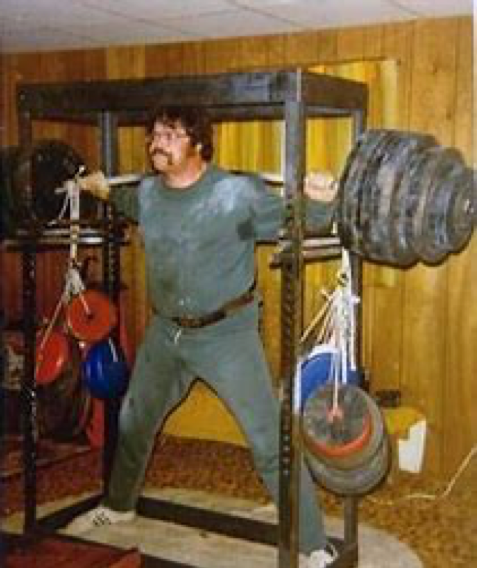

Hardcore Legend: Brad Gillingham’s father was NFL all-pro Gale Gillingham. Gale won two Superbowl’s with Vince Lombardi and the Green Bay Packers. Gale is shown doing partial barbell squats with 1400-pounds. Note extra poundage tied to the 700-pound barbell.

During a recent podcast with multi-time world powerlifting champion Brad Gillingham, host J.P. Brice asked Brad how he deals with age and aging. Brad is 53 years old and has been competing in sports his entire life. J.P. wondered how does one deal with the inevitable decline in performance, especially from an elite athletes point of view, that naturally and inevitably occur as we age?

How does one maintain the enthusiasm to strive and try, to train with the requisite ferocity? How do we generate the drive and tenacity to continue, to strain and struggle when we know our results will be substandard, compared to peak performances of years gone by?

As J.P. pointed out, many athletes simply quit. Rather than accept declining performance, they stop training altogether. In my sport, powerlifting, the landscape is littered with this type. Great lifters in their day that retired from competition and retired from training; what they didn’t retire from was the big, indiscriminate eating they engaged in when training hard, heavy and often. A massive caloric intake coupled with a sedentary lifestyle is a recipe for physiological disaster. Not coincidentally, powerlifting has an inordinately high number of ex-champions that die early.

Brad’s reply was, firstly, he was under no illusions about matching or surpassing past glories. And that was okay. Second, he had no intention of retiring, he intended on competing far into the foreseeable future. He was fine with his decreasing capacity because, as I pointed out, in comparison to other humans his age, he still kicks ass. Nowadays, rather than compare himself to all lifters he is content to compare himself to his chronological contemporaries.

Of the four roundtable podcast participants, Brad Gillingham, myself, Jim Steel and J.P. Brice, three of us (Brad, Marty, Steel) still compete. We haven’t retired from anything, despite all of us being past prime. We are fine with our diminished capacities because even diminished, all three of us are at the top of our respective age-group classifications. We compete because we have always competed. Competing puts a man on the spot. As Picasso once noted, “Periodically, a man need be jerked out of his complacency.” Periodic competition provides that periodic jerk.

Nowadays there is an incredible variety of sports that sponsor official competitions. Regardless if the competitive sport is swimming, some type or kind of running, Olympic lifting, powerlifting, bodybuilding, judo, jiu jitsu, volleyball, racquetball, tennis, softball, you name it and the sport will have classification breakdowns that enable people of all ages to compete against those approximately their own age.

There is no need to compare your current self to your 28-year old self; why quit in frustration because you can no longer exceed your all-time best efforts – unless secretly you are looking for an excuse to quit. I would posit that there are two types of elite athletes, those that live for the applause and those that live for the training.

Those that crave the adulation that comes with competitive success are far more likely to ‘retire’ than those athletes that love the training. For the later type of athlete, the training is the motivation with competition being a periodic report card. This type is far more likely to stay in the game. For the continual trainer, the eternal goal is to improve on wherever you find yourself at.

How do you conjure progress out of thin air? What combination of lifting, cardio, psyche, diet, rest or recuperative techniques do you juggle to break the stagnation logjam? How do we dynamite the sludge we find ourselves mired in? The only constant is stagnation, inertia, hemostasis, torpor. The transformative athlete struggles and strains, always seeking to extend and expand on our current capacities.

True trainers live in the eternal present, they don’t dwell on or revisit glory days, preferring to use their finite mental focus on the present, pondering the eternal question: what do we change in order to spark change?

Camus said, “Man is the only animal that refuses to be what he is.” Damn right. The trainer, living in the eternal present, seeks to become what he is not: through struggle and grinding application, the trainer revamps the body as surely as the artist uses his chisel to create sculpture. One hammer blow at a time, one workout at a time, the trainer uses self-inflicted traumatic stress to force the body to grow and get stronger. By struggling maximally, hypertrophy is triggered and body fat oxidized.

The secret to triggering muscle and strength gains is to exceed our momentary capacity, be it diminished or enhanced. Our mission is to always give 100%, no matter our age or degree of fitness or unfitness. Maximum physical effort triggers everything of value. Max efforts unleashes a hormonal tsunami as adrenaline, endorphins, serotonin, dopamine, et al, flood the bloodstream, bringing a post-workout feeling of blissful well-being. This natural high is beneficial physiologically and psychologically. Not coincidentally, intense exercise is the greatest stress reliever known to man.

All of which leads us back to the original question – how does an athlete deal with the downside of life and the natural diminishment of capacities? Regardless our capacity, it is our duty to purposefully fight and struggle in training, thereby invoking hypertrophy, muscle growth. Our duty is to fight and struggle in our cardio, thereby invoking fat oxidation. Nutrition is used to amplify training results and hasten recovery.

Competing will take anyone’s game to the next level. You only think you are training hard until you commit to compete. Weight training naturally becomes more intense as the competition approaches. Dieting naturally becomes easier and stricter as D-Day nears. Those that compete take advantage of this psychological phenomenon.

There is more good news: those that cross the Rubicon and compete come to understand that age-group competing is no big deal. What those on the outside with their noses pressed against glass fail to grasp is that the actual competitions are not all that stressful. All the other athletes are so concerned with their own game, their own performance, that no one really pays attention to you – it is not as if a camera crew is following you around, recording your every move. Factually, no one really cares.

A bit anticlimactic? Perhaps for the adulation junkie that lives for the applause. For the trainer that lives to train and loves to train, competition is the report card, not the goal. Want to periodically get jerked out of your torpor and complacency? Find a sport. Commit to compete. Put yourself on the spot. Take your game to the next level.

About the Author

As an athlete Marty Gallagher is a national and world champion in Olympic lifting and powerlifting. He was a world champion team coach in 1991 and coached Black's Gym to five national team titles. He's also coached some of the strongest men on the planet including Kirk Karwoski when he completed his world record 1,003 lb. squat. Today he teaches the US Secret Service and Tier 1 Spec Ops on how to maximize their strength in minimal time. As a writer since 1978 he’s written for Powerlifting USA, Milo, Flex Magazine, Muscle & Fitness, Prime Fitness, Washington Post, Dragon Door and now IRON COMPANY. He’s also the author of numerous books including Purposeful Primitive, Strong Medicine, Ed Coan’s book “Coan, The Man, the Myth, the Method" and numerous others. Read the Marty Gallagher biography here.