The Athletic Woodshed

Reinventing oneself

Before electricity and gas came to the rural south, most heating was done by woodstove and most folks had a woodshed to cure green wood and keep cured wood dry. The woodshed was built away from the house in case it caught fire. In the old south being sent to the woodshed meant you had done something really bad and had earned a whipping. While getting whipped, rather than subject others in the house to having to listen to your screaming, crying, and caterwauling, the whipping was administered away from the main house in the woodshed.

The artistic woodshed has a different definition. For elite jazz musicians, going to the woodshed meant isolating oneself for a protracted period, no public playing and limited interaction with other humans. The woodshedding musician created a creative, stress-free environment. They paid all the bills ahead of time, had a stash of cash available for groceries, Chinese carry-out and alcohol. They would settle into this creative environment for an extended stay.

The artist avoided societal contact and lived in purposeful solitude. All life and living were centered around the highly concentrated, marathon daily practice sessions. These sessions were designed to break the musician through to the next level of technical virtuosity.

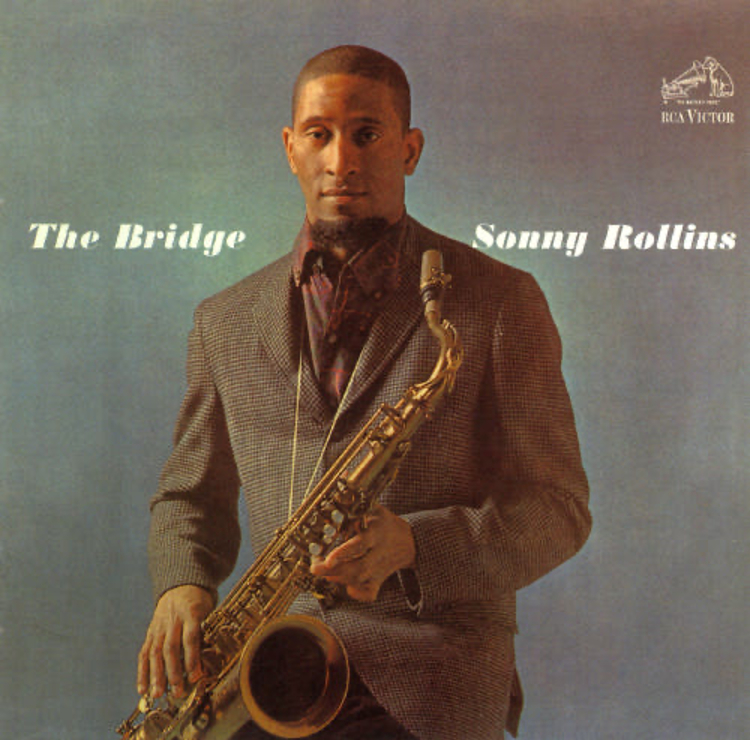

My favorite artistic woodshedding story involves jazz tenor saxophone God Sonny Rollins. By age 29, Sonny was a jazz superstar. At the height of newfound fame and adulation, he quit without explanation. What was it that drove a man at the top of his game to withdraw from the game? Artistic dissatisfaction. Despite being only 29, Rollins had been a fixture on the Jazz scene for a decade. He had a fully developed style, a style that the world loved. It was a style he had come to detest.

For Sonny, his patented middle-register, super-fluidity felt stale; robotic and emotionless. He had invented and perfected a unique approach that was once vibrant, inquisitive, and spontaneously explosive. What was once wild and unpredictable now felt clichéd and stale. Not that anyone other than Sonny would notice. His technical virtuosity dazzled fans and critics alike and obscured the fact that, as far as he was concerned, he was creating passionless elevator music. Wikipedia flushes out what happened next…

In 1959, feeling pressured by the unexpected swiftness of his rise to fame, Rollins took a three-year hiatus to focus on perfecting his craft. A resident of the Lower East Side of Manhattan with no private space to practice, he took his saxophone up to the Williamsburg Bridge to practice alone: "I would be up there 15 or 16 hours at a time spring, summer, fall and winter". His first recording after his return to performance took its name from those solo sessions. The album was called The Bridge. It was hailed as a milestone.

Rollins found a spot along the long bridge walkway where he could be shadowed from the blazing sun in August and sheltered from face-stinging snow flurries in December. Rollins had a lot to forget. He had to unlearn all his famous licks and phrases. He had to forget all his musical clichés and tics, all his tendencies and conditioning had to be exorcised.

It took three years to create his new style. Oddly, once he mastered his new style it breathed freshness into his old style. Now he was the master of two styles that he could keep separate or mix and match. Sonny Rollins had gone to the artistic woodshed and succeeded in engineering a stylistic and artistic miracle.

Upper body specialization works! he no longer looked like “a muscular dwarf riding an ostrich”

One great example of a man going into the athletic woodshed to reinvent himself was that of strength grand master Kirk Karwoski, six-time IPF world powerlifting champion, seven-time USPF national champion and holder of multiple world records. Kirk’s journey was a great example of an athlete reinventing himself and successfully breaking through to stratospheric levels of athletic excellence.

By the time Kirk was 20-years old he was winning major titles in the second-most powerful and influential powerlifting organization in the United States, the ADFPA. He broke the 800-pound barrier in the squat while weighing 240-pounds. His other lifts lagged, low 400s in the bench press and barely over 600 in the deadlift.

Kirk could have chosen to remain one of the big fish in this smaller organizational pond. Kirk wanted to play in the NFL of powerlifting: The United States Powerlifting Federation. The USPF was the national affiliate of the International Powerlifting Federation, the Mac Daddy of all powerlifting federations.

Kirk’s dream was to compete and win the biggest title in all of powerlifting, the IPF world championship. For Kirk to compete at an IPF World Championships, he would first have to win a USPF national competition and be selected as a member of the United States squad. The US team then competes at the IPF world championships against 36 other member nations for individual titles and the world team title.

Kirk made a life decision: he would compete in the USPF. He was leaving at the top of one organization to start at the bottom of another organization. He was under no illusions. It was during this transitory period he sought me out as a coach. I outlined the lifts he would need to do to be competitive and how he would have to do them: the judging would be far stricter in the USPF than anything he had been subjected to thus far.

Kirk went to the athletic woodshed: he rearranged his entire life so that everything in it revolved around his lone goal: to win a USPF national championship. Everything was made possible by his job. Kirk was a union printer. He worked hard and made good money. By working a half day on Saturday, he was off all day Monday, creating a 4.5-day workweek. He saved his money and purchased a fine little condominium. He settled in for a long siege; he would pursue his goal no matter how long it took.

This was the beginning of a Ulysses-like, ten-year epic power odyssey, a decade of utter and complete woodshedding, woodshedding as a lifestyle. Every week, week in, week out, he adhered to a robotic existence: train, eat, sleep, go to work, repeat.

Not that Kirk was any kind of monastic saint, he was a good-looking young man in his 20s and Friday and Saturday nights were for partying. Elite alpha athletes tend to have big appetites and large capacities and not just in training or eating. Kirk was no exception.

Initially. he had a lot of “unlearning” to do. His lifting techniques were wild, erratic, and inconsistent, in keeping with his then-personality. I slowed him down, introduced him to our archetypical squat/bench/deadlift signature styles and got him to concentrate on cookie-cutter five-rep sets.

He got into a deep groove: most every morning he would head from his bachelor pad into work. Four times a week he would train for 60-90 minutes at the Maryland Athletic Club. Most days he would eat one big meal at the Horn & Horn buffet. Kirk was quite comfortable in the kitchen and would mix up some great power dishes, always meat and vegetables, often with flavored rice.

Kirk stayed in this deep pocket, this zone of athletic creativity and selectivity for ten years. Each successive year he improved and improved to a remarkable degree: his lifts got cleaner and deeper; his crisp techniques muscled him up. I introduced him to Ken Fantano, who got Kirk squared away on his bench press technique. Karwoski had incredible legs and he had to work twice as hard to bring up his badly lagging upper body.

One training partner who shall remain nameless (Marshall Peck) unkindly once said of Kirk (early in his career) that with his giant thighs, huge calves and Kardashian-like glutes, his much smaller (but muscular!) upper body made him look like “a muscular dwarf riding an ostrich!” Ouch!

As the years passed by Kirk pushed his 420-pound bench press up to 600-pounds. He pushed his 45-degree strict incline press upward to 445 x 5 reps. He curled a pair of 100s for 10 reps and guess what? No more disproportionality issues. Kirk upped every aspect of his game. Kirk developed a “power dieting” regimen, one designed specifically for him by a friend, pro bodybuilder Anthony D’Arezzo.

Kirks newfound dietary expertise allowed him to become adept at controlling his bodyweight. He won world titles and set world records in both the 242 and 275-pound weight class. Kirk is one of only three men to win national powerlifting championships in three weight classes (242, 275 and superheavyweight.) Karwoski could easily have added another 3-4 national and world titles to his scalp pelt. He grew tired of being in the eternal woodshed. A decade was enough.

Reading about the fanatical dedication of men like Sonny Rollins and Kirk Karwoski inspires us mere mortals to take our own game to the next level. Who couldn’t use more concentrated effort in their training? Who couldn’t use a tad more fanaticism and fierceness in their transformational efforts? Dramatic results do not occur in response to casual efforts.

About the Author

As an athlete Marty Gallagher is a national and world champion in Olympic lifting and powerlifting. He was a world champion team coach in 1991 and coached Black's Gym to five national team titles. He's also coached some of the strongest men on the planet including Kirk Karwoski when he completed his world record 1,003 lb. squat. Today he teaches the US Secret Service and Tier 1 Spec Ops on how to maximize their strength in minimal time. As a writer since 1978 he’s written for Powerlifting USA, Milo, Flex Magazine, Muscle & Fitness, Prime Fitness, Washington Post, Dragon Door and now IRON COMPANY. He’s also the author of multiple books including Purposeful Primitive, Strong Medicine, Ed Coan’s book “Coan, The Man, the Myth, the Method" and numerous others. Read the Marty Gallagher biography here.