Cardio & Heart Rate – would you lift weights without knowing the poundage?

Tech makes it easier to achieve your cardio training goals!

I have been an enthusiastic user of heart rate monitors since they first began appearing in the 1990s. The heart rate monitor allowed athletes to determine how hard the heart was working in relation to the work being done. The use of a heart rate monitor enabled an athlete, for the first time, to assign a numeric value to the intensity of the cardiovascular effort.

Intensity was the missing piece to the aerobic puzzle. Now, in addition to identifying mode, duration, and frequency, the athlete could now place a specific numerical value on the intensity, the difficulty, the degree of effort and exertion. Once identified, intensity could be preplanned, checked in real time, and analyzed retroactively. As I have noted previously, doing aerobic exercise without knowing the intensity is akin to lifting weights without knowing the poundage.

Classical Resistance Training Periodization

In resistance training everything is numeric: sets, reps, session duration, session frequency, poundage, amount of rest between sets, etc. Because everything is numeric, resistance training lends itself to periodization, i.e. athletic preplanning. A classical periodized resistance training cycle might consist of a 12-week macro-cycle with three, 4-week micro-cycles tucked inside.

Periodization is the art and science of conjuring progress and then sustaining it for months on end. Periodization adherents typically use a 12-week training cycle designed to peak muscle and strength. The classic strategy is to begin the cycle 10% below capacity and seek to end the 12-week program 10% over current capacities.

In a classical periodization scenario, one of our lifters, a 24-year old with a 400-pound squat, sought a 450-pound squat in his upcoming competition. This would represent a fantastic 12.5% increase in 90-days. This type of strength increase required our 154-pound athlete to add muscle: at 154-pounds with 25-inch thighs, he did not possess enough muscular firepower to accomplish the task.

The young athlete embraced this inconvenient truth and committed to moving up a weight class. He added 11-pounds of lean muscle mass in 90-days, a pound per week, by combining a high-calorie, high protein bodybuilder-style diet with power training and a complimentary, consistent, no-stress lifestyle. He did not smoke or drink and was a clean eater. He consumed a lot of Parrillo Optimized Whey protein powder and 50-50 Plus, the Parrillo post-workout replenishment powder.

We strength train one time a week. After 3-5 warmup sets, our lifter would hit the targeted periodization goal for the week, the top set. One big set per week. That is it, insofar as squatting for the entire week. Hit the periodized goal for the week, move onto the next lift of the session, repeat till done, see you next week.

The first four weeks of the cycle were dedicated to 10 and 8 rep top sets. The lesser poundage enabled technical refinements and the establishment of full ROM. The middle four weeks concentrated on 5-rep sets. This is where the real strength training began. The final four weeks utilized a “repetition taper” to peak size, strength, and performance.

Each week our athlete purposefully added a pound (no more, no less) of bodyweight. By staying in a calorically positive state, anabolism was established. The goal is for the lifter to stay in a state of continual positive nitrogen balance. This is the ideal metabolic status, the fertile field needed for muscle growth that prefigures strength increases.

This is a partial periodized template, the full spread sheet would include “cycled” bench press, deadlift, and overhead press. By the way, our young lifter made his 450-pound squat; this weighing a thick and muscled-up 165-pounds. He also made his first 300-pound bench and pulled his first 500-pound deadlift.

| Week | Squat | Bodyweight |

| 1 | 295 x 10 | 154 |

| 2 | 305 x 10 | 155 |

| 3 | 315 x 8 | 156 |

| 4 | 325 x 8 | 157 |

| 5 | 345 x 5 | 158 |

| 6 | 355 x 5 | 159 |

| 7 | 365 x 5 | 160 |

| 8 | 375 x 5 | 161 |

| 9 | 390 x 4 | 162 |

| 10 | 405 x 3 | 163 |

| 11 | 420 x 2 | 164 |

| 12 | 450 x 1 | 165 |

Heart Rate Periodization: cycling cardio

How can strength training periodization protocols be adapted for aerobic exercise? How would an athlete set up an aerobic approach that would replicate a strength training periodized cycle? As always, four elements need be identified: mode, duration, frequency, intensity. There are two types of generalized cardiovascular exercise: steady-state and burst.

- Steady-state: attain and retain a steady pace for the duration of the session. Over time, and with practice, the steady-state pace is systematically increased.

- Burst or interval: regardless the mode, generate an all-out effort for a short duration. Sprint, recover, sprint again.

This template is for steady-state activities. This particular periodized template was designed for a 40-year old out-of-shape individual looking to ease back into fitness. The person had been a good athlete 20 years ago. Formerly fit, this approach reawakened his dormant muscle memory.

Steady-State Cardio Template

Mode: running

Bodyweight: 200-pounds

Current deadlift maximum: 225

| Week | Frequency | Duration | Intensity | Bodyweight | Deadlift |

| 1 | 3 x weekly | 20 | 60% | 199 lbs. | 165 x 5 |

| 2 | 3 | 22 | 62.5% | 198 | 175 x 5 |

| 3 | 4 | 24 | 65% | 197 | 185 x 5 |

| 4 | 4 | 26 | 67.5% | 196 | 195 x 5 |

| 5 | 4 | 28 | 70% | 195 | 215 x 3 |

| 6 | 5 | 30 | 72.5% | 194 | 225 x 3 |

| 7 | 5 | 32 | 75% | 193 | 235 x 3 |

| 8 | 5 | 34 | 77% | 192 | 245 x 2 |

| 9 | 6 | 36 | 80% | 191 | 255 x 2 |

| 10 | 6 | 40 | 80% | 190 | 265 x 1 |

*our trainee began week 1 weighing 200.4 – at the end of week 1, he weighed 199, where we begin

Over the life of this 10-week, 70-day cycle, weekly sessions were systematically doubled, from three to six; session length doubled, from 20-minutes to 40-mimutes; intensity increased by 20%. Our trainee dropped 10-pounds of body fat and added 100-pounds to his deadlift training poundage. His best deadlift commencing the cycle was 225-pounds. His 265 effort in week 10 represented a 18% increase.

Initially, his newness to running limited him to trotting along. As he shaped up and acclimatized, his mild trotting morphed into serious, sweat-producing jog-running. Sessions were done in the early morning to take advantage of the “fasted cardio” effect. If aerobic exercise is done coming off the sleep fast, the body will exhaust glycogen and when glycogen (emulsified carbohydrates) is exhausted, the body commences burning its second-favored fuel source, stored body fat.

As the cardio session unfolds, our business exec’s goal was to stay near, at, or slightly above, the session’s preplanned target heartrate. As the session commences, the chest strap, hooked up to a phone app, begins counting heartbeats. If, for example, during a 20-minute session the athlete’s heart beats a grand total of 2,200 times, the app would do the math and relate that they attained a “blended average” of 110-beats per minute for each of the 20-minutes in the session.

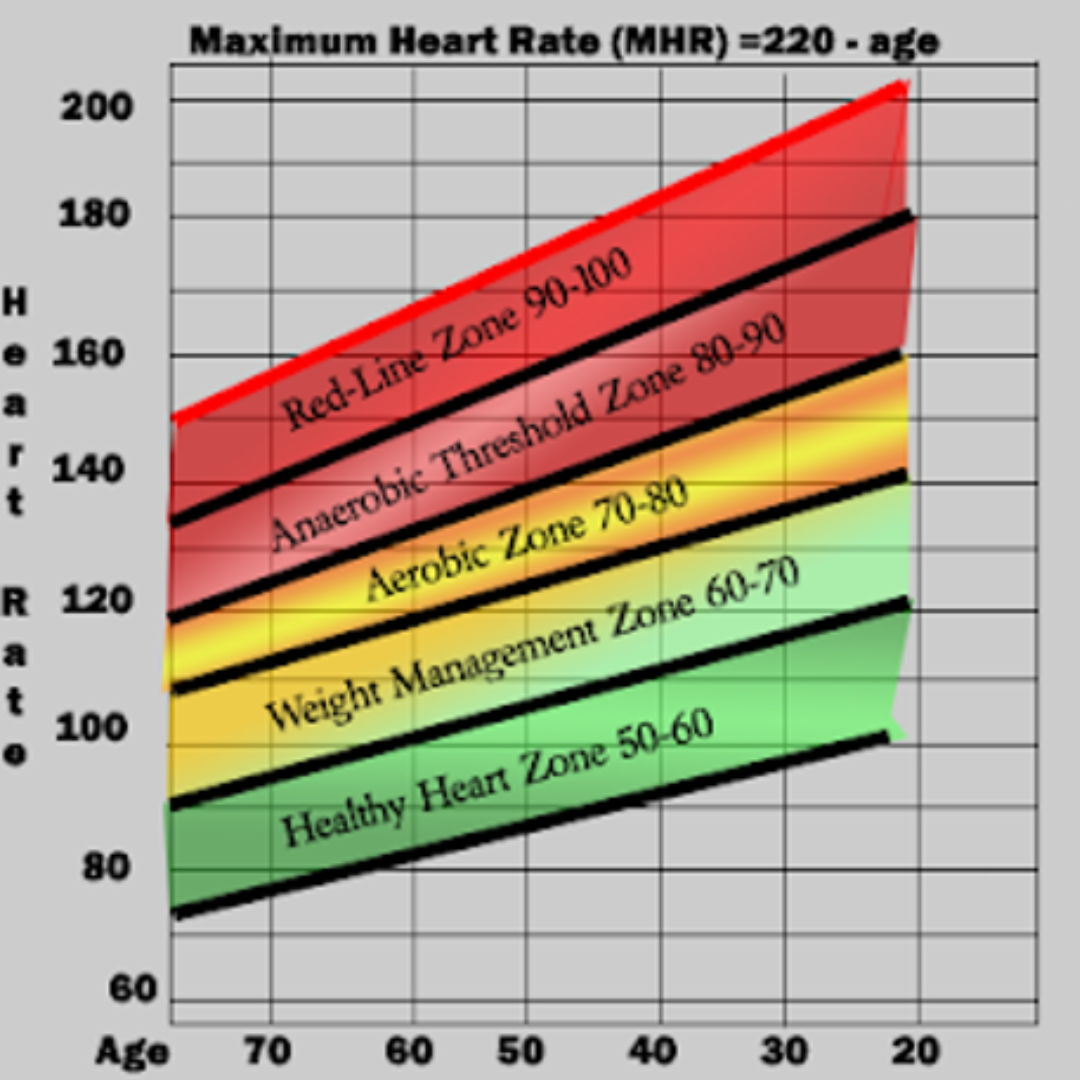

To assign a further numeric value to the effort, our 40-year old now converts his 110-beat per minute blended session heart rate average into a percentile: 220 minus the athlete’s age (40) creates a number – in this case 220 – 40 = 180. Ergo, 180 equates to a 100% heart rate maximum for a 40-year old. 110 is 60% of 180. The goal is to work at 60% of 100% capacity in the first session.

During the 20-minute session, the athlete pays attention to his heart rate in real time. Where is he in relation to the predetermined goal? If the monitor indicates his heart is beating 101 times a minute, he needs to pick up the pace. If it reads 126, he can back off the pace a bit. Each successive week, the goal is to slightly increase the pace, the intensity.

Each week requires a slight, 2.5% bump in intensity. The following week the goal was upped from 60% to 62.5%. Numerically, this required he increase his blended-session average from 110 beats-per-minute (60%) to 113 (62.5%) beats per minute. Not much, quite attainable for someone that has three successful 60% sessions under their belt from the previous week.

The key to successful periodization is establishing realistic goals and reverse-engineering a periodized game plan. Start off easy and establish an exercise rhythm and flow. Each week, the athlete asks of themselves a little more. The elephant is eaten one bite at a time.

There is a difference between exercising and training. Training requires thoughtful preplanning to reach a predetermined goal, a performance and/or physique goal. Without periodized planning, every “exercise” session is Ground Hog day, doomed to never doing more than treading water. Without a plan there can be no sustained progress.

About the Author - Marty Gallagher

As an athlete Marty Gallagher is a national and world champion in Olympic lifting and powerlifting. He was a world champion team coach in 1991 and coached Black's Gym to five national team titles. He's also coached some of the strongest men on the planet including Kirk Karwoski when he completed his world record 1,003 lb. squat. Today he teaches the US Secret Service and Tier 1 Spec Ops on how to maximize their strength in minimal time. As a writer since 1978 he’s written for Powerlifting USA, Milo, Flex Magazine, Muscle & Fitness, Prime Fitness, Washington Post, Dragon Door and now IRON COMPANY. He’s also the author of multiple books including Purposeful Primitive, Strong Medicine, Ed Coan’s book “Coan, The Man, the Myth, the Method" and numerous others. Read the Marty Gallagher Biography for a more in depth look at his credentials as an athlete, coach and writer.