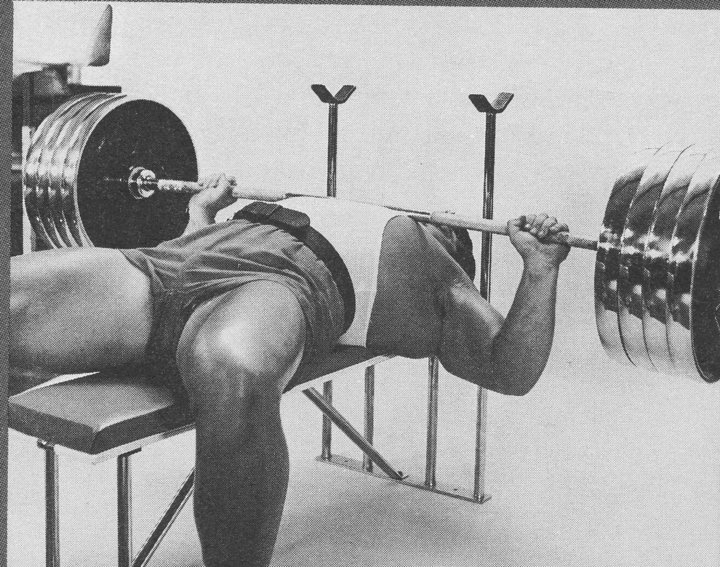

Barbell Bench Press 101

Commonalities and Tactical Tips for Bench Pressing

I mentored under one of the world’s best barbell bench pressers and I have trained with a lot of incredibly good bench pressers, world champions. I myself have trained many a world-class bench presser. Yet I personally have always sucked at the bench press, for a variety of reasons. My best shirtless bench press was a paltry 440-pounds. Meanwhile, my competitors routinely bench pressed 100 pounds more than me. Most competitive powerlifters start off as good bench pressers that get drawn into the other two lifts. I was an Olympic weightlifter that had a good squat and lots of pulling power applicable to deadlifting, with zero prone pushing experience. Regardless of my own bench inabilities, the strategies taught to me, those I redirected, passed along, used by me to teach others, have always gotten sensational results – when implemented with the requisite tenacity and fire. Here are some invaluable tactical tips that were given to me by the greats and that are used to this day by our young lifters.

Pull the bar down: most bench pressers ‘throw away’ the negative portion of the bench press repetition. If the bench presser relaxes the benching muscles during the lowering, the lack of tension makes lower easy - but dilutes any muscle growth or strength-infusing attributes associated with the eccentric negative. I was taught (and teach) to “pull the barbell down,” purposefully create tension, actively resist the payload as it is being lowered. Tension amplifies the muscle-building strength-enhancing benefits associated with a resisted negative. I was taught to apply greater and greater resistance, “put on the brakes” as the payload approaches the chest. Eccentric tension, in varying degrees, is maintained throughout and maximized at the ‘turn-around,’ where eccentric lowering becomes concentric pushing. When the lifter breaks his elbows to begin the negative, we tell them to think ‘slow…slower…slowest!’ as poundage approaches the turnaround. At the turnaround the lifter can either pause the poundage or touch-and-go. Don’t throw away the bench press negative.

Master three distinct grip widths: Hugh Cassidy once said, ‘the best assistance exercise for a lift is another lift that most closely resembles the primary lift.’ Therefore, the best assistance exercise for a competition-style bench press is more flat benching - using different grip widths. Everyone has a favored bench press grip width. The best bench assistance exercise would be more benching using a wider grip-width and/or a narrower grip. I was attracted to Ed Coan and Doug Furnas’ philosophy of strength when I was first exposed to it, because, like Hugh, they used wide-grip and narrow-grip benches to augment their “competition grip width.” Cassidy and Coan came to the same benching conclusions completely independent of one another. Doug Furnas learned his benching from world champion Dennis Wright (500 raw bench at 198.) Doug would pause his wide grips and touch-and-go his narrow grips. Wide grip bench presses, particularly when paused, isolate the pectorals and emphasize the bench press start, the beginning of the concentric; narrow-grip benches emphasize the triceps and the lockout. No need to pause narrow-grips as all the stress occurs at the top during lock-out.

The Arc: The bench negative is “pulled down” to the highest point of the expanded chest. The bar came down in an arc, from over the eyes at lockout to low on the chest, at the highest touch point. There is a downward arc that is reversed on the concentric, push phase. The upward push uses a mirror-image precision pathway of a tension-filled lowering. I was taught to push up and back, reversing the arc as the power bar is pushed back to lockout: arc on the descent, arc on the ascent. I thought it was extremely serendipitous that when I began training with bench press grand maestro Ken Fantano (633-pound raw paused double) Ken too stressed the arc. It was divine confirmation. A rearward arc on the way up assists the triceps through the sticking point by allowing the poundage to move rearward and upward, thereby improving triceps leverage. Too many bench pressers lower to a touch point too high up on chest, towards the neck. The great bencher lowers to the densest part of the lower pec: a maximally expanded chest and a high touch point shorten the rep stroke. Up and back is a stronger motor-pathway than straight up. Also: powerhouse bench pressers do not flare their elbows, they tuck them inward. At the turnaround, the triceps are wedged against the expanded lats, making for an optimal push platform to commence the concentric.

The press-behind-the-neck and the Incline Press: a lot of great bench pressers get incredible results from diligent practice of the barbell press-behind the neck. By pushing up their PBN their bench press improves. As improbable as it sounds, Ed Coan and Joe Ladiner were both capable of 400-pounds in the seated press behind the neck. These guys were doing 350 for 5 reps and most amazing: they “only” weighed 220 and 235 pounds. These men were not 300-pound giants. A lot of people are physically unable to perform the PBN due to genetic shoulder construction. I am one. A lot of super strong bench pressers also swear by the incline bench press. My boy Kirk Karwoski was a 600-raw bencher and could rep 445 for five in the strict, paused 45-degree incline barbell press. He was a big fan of the exercise: his procedure was to work up to one big set of 5-reps and bag it. The greatest bencher I ever trained with, Ken Fantano, felt the bench press was “a technique lift.” He benched on Sunday and would perform heavy, super strict incline dumbbell presses midweek. He used dumbbells and he paused his reps. Ken would work up to a mind-boggling 400-pounds (two 200-pound dumbbells) for six paused reps. He told me that strict inclines using dumbbells “give me the contraction I’m looking for.” Ken took benching to a high art and he took bench assistance work to a high art. The takeaway is the monster benchers would use the PNB or Incline, barbell or dumbbells, to push up the competitive bench press. Hit one of these two lifts 2-3 days after benching.

Once a week benching: In the golden era of bodybuilding, when Arnold and Franco, Robbie, Mentzer and Zane were all running around Muscle Beach, this in the mid to late 60s, the boys trained every muscle threetimes a week. Imagine, benching, doing arms and shoulder work in three separate training sessions each week, all year round. The accepted conventional wisdom of the time (completely fallacious) was that unless a muscle was trained every 48-72 hours, that muscle would shrink, degrade, weaken. Guys like Bill Pearl and Reg Park were doing their entire leg and back routines three times a week. In the 1970s, powerlifters reduced the volume from thrice to twice, and got great gains in power, size and strength. In the 1980s, a new breed of power athlete reduced blasting away at a competition lift from twice to once weekly. These men made astounding leaps in strength, size and power and created records that have not been equaled or exceeded to this day. Bodybuilders like Dorian Yates adopted the once weekly per body part strategy and grew gargantuan. If you bench press hard and heavy, if you use various grip widths for bench assistance, if you work arms, biceps and triceps, if you engage in intense shoulder work or heavy incline pressing - then you need to limit benching to once a week.

Have a plan: the surest way to build the chest, arms and shoulders is to obtain a monster flat bench. In order to make substantial upper body muscle gains, you need to figure out a way to make substantial bench press gains. If a man has a certain degree of muscular development in his chest shoulder and arms with a 200-pound bench press weighing 170-poubds, that same man will build a tremendous amount of pec, deltoid and tricep muscle if he somehow finds a way to push his 200-pound bench press upward to 300-pounds. This does not just miraculously happen. The classical way in which to build a lift is to build the body. The 170-pound man with the 200-pound bench press is NOT going to bench press 300-pounds weighing 170, he doesn’t have enough muscular firepower: he needs bigger chest, shoulder and arm muscles. The classic approach is to couple a bench press specialization program with a nutritional “mass-building” phase. The athlete purposefully “stays calorie positive” and adds quality bodyweight. If the eating is “clean,” high in protein and devoid of refined carbs and sugar, weight gain will be lean muscle mass, particularly if the diligent athlete performs regular cardio. If that 200-pound bencher, weighing 170, pushes his lean bodyweight up to 185 pounds, adding 1 pound a week of bodyweight per week for fifteen straight weeks, this muscled-up athlete will manhandle 250 to 260 in the bench press. Repeat the process later in the year, push from 185 to a lean 200-pounds of bodyweight and behold! The 300-pound paused bench press becomes a reality! But you are a whole different man weighing 200 than you were at the 170-pound starting point. All this takes planning like you are running a military campaign. You are wasting your time trying to find some magic workout routine that jumps your bench 100-pounds without you having to gain an ounce of bodyweight. To get bigger you need to get stronger. To get stronger, you have to get bigger. Have a plan and stick to it.

About the Author

As an athlete Marty Gallagher is a national and world champion in Olympic lifting and powerlifting. He was a world champion team coach in 1991 and coached Black's Gym to five national team titles. He's also coached some of the strongest men on the planet including Kirk Karwoski when he completed his world record 1,003 lb. squat. Today he teaches the US Secret Service and Tier 1 Spec Ops on how to maximize their strength in minimal time. As a writer since 1978 he’s written for Powerlifting USA, Milo, Flex Magazine, Muscle & Fitness, Prime Fitness, Washington Post, Dragon Door and now IRON COMPANY. He’s also the author of numerous books including Purposeful Primitive, Strong Medicine, Ed Coan’s book “Coan, The Man, the Myth, the Method" and numerous others. Read the Marty Gallagher biography here.