Technical Fixations In Weightlifting

Signature techniques and archetypes developed in pursuit of world records

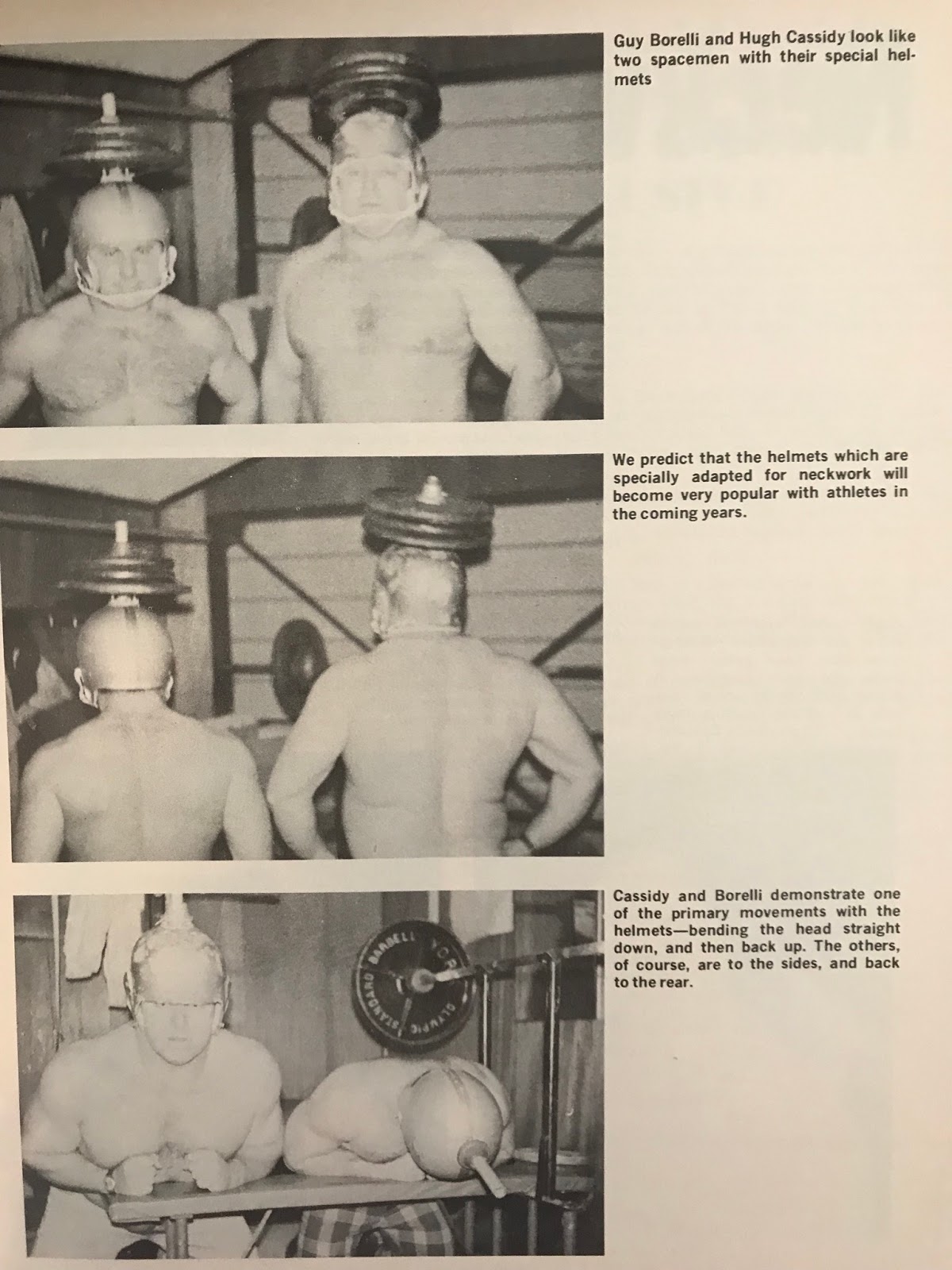

My mentor: “Take us to your leader!” Hugh Cassidy used to walk around his farm-ette, going about his business, with 50-pounds on the spike. Question: why does a guy with a 21-inch neck feel the need to do neck work?

Olympic lifters have a necessary fixation on technique. As the extreme exponents of explosive strength, the Olympic weightlifter uses highly specific techniques to generate upward barbell velocity. In a bit of an oversimplification, Olympic lifters learn how to “fling and catch” a barbell. Olympic weightlifters do not lift a barbell, they accelerate a barbell. The true Olympic weightlifter pulls or pushes on the barbell with such force that were the lifter to remove their hands from the bar at any juncture during a pull or push, the barbell would continue its upward path.

This nanosecond of upward momentum allows the lifter the split-second needed to hurl themselves underneath the bar and “catch it” during a snatch, clean, or during a jerk. The Olympic lifter has highly specific techniques for creating upward velocity and highly specific techniques for catching and recovering with the barbell.

If the powerlifter takes his hands off a deadlift, that bar drops like a guillotine. No need for explosiveness or momentum during a powerlift; the powerlifts are examples of low-end torque whereas Olympic weightlifting is an example of horsepower. If you want to pull a stump out of the ground, call a powerlifter; if you want to go 220 miles an hour at Lemans, call an Olympic weightlifter. You don’t use a Ferrari to tow a 4,000-pound mobile home and you can’t expect to cruise at 130 miles an hour on the Autobahn in a dump truck.

As a young boy I wanted to become an Olympic weightlifter. Having no formal coaching, I was self-taught and actively sought to improve my technical prowess in the overhead press, snatch and clean and jerk. I studied and pondered. These highly technical, compound multi-joint exercises require every muscle on the body to activate to varying degrees. The lifts also require expert coaching.

A snatch, a squat clean, a proper jerk, or push-jerk, is every bit as complex and difficult to learn as (and far more dangerous) perfecting a golf swing, tennis serve, or baseball bat swing. The lure of technique is simple: become more technically proficient and improve performance. An elite Olympic lifter need only pull a barbell to pec height to snatch it; they need only pull the bar to belly-button height to clean it. In Olympic lifting, weaker men with great technique routinely make mincemeat of much stronger men possessing terrible technique.

Strong men unable to master the complexities of Olympic lifting defected to powerlifting in droves. Powerlifting was a sport far less technically demanding. Another lure of powerlifting: an elite Olympic weightlifter needed to be in the gym 4-6 times a week (optimally) to drill and instill quick-lift skill. Honing complex techniques are something that requires lots of time and lots of reps. The powerlifters made sensational gains training only 2-3 times a week. The dramatically heavier poundage used required more time to fully and completely recover, session to session.

Another reason for the flood of defections from Olympic lifting into powerlifting: men preferred the physiques of the muscled-up powerlifters to the physiques of the top Olympic weightlifters. A weightlifter did zero chest training and no arm training whatsoever. Small arms and underdeveloped pecs attached to the Olympic weightlifters big legs and excellent back muscles created disproportional physiques that did not inspire.

The bulky, hulking powerlifters did lots of tricep work to augment the bench press. The Powerlifter spent less time in the gym, required less emphasis on technique, obtained more muscle, built a massive chest, big guns and a proportional physique. No wonder a mass exodus occurred from one iron sport to another when powerlifting became an official AAU sport.

My powerlifting mentor was an ex-Olympic weightlifter who took with him a reverence for technique. Hugh Cassidy transferred his attention to exercise detail and style and applied it to the three powerlifts: the squat, bench press, and deadlift. Hugh already had an excellent squat and deadlift heading into powerlifting. Olympic weightlifters squat deep and squat often. The ultra-deep squat is the most practiced “assistance exercise” for the three Olympic lifts. Olympic lifters develop massive back muscles from all the pulling they do, fantastic for deadlifting.

Leg strength is crucial for being able to arise after squat cleaning 1.5 times or double your bodyweight. Leg power is required to arise from a squat snatch when your glutes are pinned six inches off the floor. Weightlifters perform front squats and back squats two to three times a week. The deadlift comes naturally to an Olympic lifter, and they have the muscular artillery to pull big deadlifts right away.

Deep squatting and heavy pulling gave ex-Olympic weightlifters a leg up in the new sport of powerlifting, adopted by the AAU as an official sport in 1965. Bodybuilders proved to be terrific bench pressers, top AAU bodybuilders like Bill Seno (450-raw bench press, 198-pound class) were setting national bench press records right and left.

Those early power pioneers had no mentors to draw upon as they were the first generation of competitive lifters. Power pioneers forged their own paths. I had Cassidy’s experience to draw upon, he gave us his signature techniques and battle-proven tactics. I stood on his shoulders. He stood on no ones’ shoulders.

What is an optimal technique? In powerlifting and weightlifting, the lesser competitors take their technical cues from the world champions and world record holders. Performance sculpts technique. The optimal technique delivers the optimal results. Certain commonalities emerged when comparing techniques of the champions. Those commonalities merged and formed a consensus. Technical archetypes emerged from the fog of potentialities and possibilities. Empirical feedback always guides and molds a system.

Cassidy created a brutally simplistic power training template. His acolytes gathered twice a week to train in extended sessions underpinned with ample calories and loads of restorative rest. Our quest was to add muscle mass, add bodyweight, to become larger, stronger, more muscular. Programing was elemental periodization: create numerical lifting and bodyweight goals, reverse engineer, create weekly lifting goals that approach the overall goal incrementally.

Those of us that were able to adhere, those that trained with the requisite ferocity, those that continually consumed copious calories and slept long, deep, and often, invariably made mind-blowing gains in muscle and power. The common characteristics Cassidy codified were simple and logical….

- Squat: deep squatting builds powerhouse legs. Open the stance width. The knees stay over the ankles as opposed to letting the knees travel forward ahead of the toes. The barbell should never get ahead of the knees. Knees are “pinned out” during both the descent and ascent. Great care is taken to not allow the knees to collapse inward as the squatter struggles through the sticking point. One breath per rep. Eyes are laser-focused and unwavering on a single visual focus point.

- Bench press: four definable bench styles; touch-and-go, paused, narrow-grip touch-and-go, and dumbbell benching (both paused and T&G.) Our school uses an arc, on both the eccentric lowering and concentric push phase. The arc bar path lessens the strain on the triceps during lockout. Feet are set forward of knees, torso, glutes, thighs, tensed. The lifter “pulls” the barbell down to the torso, building coiled tension. The barbell is exploded up and back, using compensatory acceleration.

- Deadlift: Cassidy championed a narrow-stance, “one fist-width between-heels.” Cassidy’s reasoning that a narrow stance enabled the shortest possible rep stroke: conversely, spread the feet wide and the hands are forced further outward on the barbell, lengthening the rep stroke. Cassidy stressed an upright start position that required the legs break the barbell from the floor, allowing the hip-hinge to stay in reserve and fire when the bar touches the lower kneecaps. Never let the shoulders get ahead of the barbell.

Assistance work: nothing for legs; stiff-leg deadlifts, heaves for the back; seated overhead dumbbell press for the shoulders; bicep curls, tricep work.

Revisiting core weightlifting techniques, i.e., how you perform a resistance training exercise, is a guaranteed way to generate progress. Making an exercise more difficult by being more technically precise is a proven progress stimulator. The main inhibitor is the ego hit when a trainee tightens up a technique and is only able to use 70% of previous poundage. Strive to generate strict, precise, cookie-cutter reps in the squat, bench press, deadlift, overhead pressing and power clean. Become a technical stickler and watch as your physique and performance are taken to the next level.

About the Author - Marty Gallagher

As an athlete Marty Gallagher is a national and world champion in Olympic lifting and powerlifting. He was a world champion team coach in 1991 and coached Black's Gym to five national team titles. He's also coached some of the strongest men on the planet including Kirk Karwoski when he completed his world record 1,003 lb. squat. Today he teaches the US Secret Service and Tier 1 Spec Ops on how to maximize their strength in minimal time. As a writer since 1978 he’s written for Powerlifting USA, Milo, Flex Magazine, Muscle & Fitness, Prime Fitness, Washington Post, Dragon Door and now IRON COMPANY. He’s also the author of multiple books including Purposeful Primitive, Strong Medicine, Ed Coan’s book “Coan, The Man, the Myth, the Method" and numerous others. Read the Marty Gallagher Biography for a more in depth look at his credentials as an athlete, coach and writer.