Multidimensional Training Recovery

New Old Conundrum

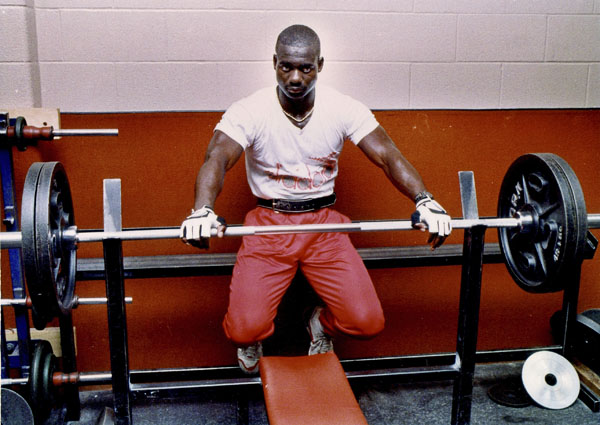

Ben Johnson (above) was the world’s fastest man and (not coincidentally) also the world’s strongest sprinter, capable of a 402-bench press weighing 180. He stood 5-10. He ran 9.79 world record in 1988. Experts felt that had Johnson not thrown his hands overhead in victory with ten yards to go he would have posted a 9.6 time. How great is that? Usain Bolt’s 9:58 WR has stood since 2009.

Training recovery equates to Optimal: on a whim, I recently picked up my well-worn copy of Charlie Francis’ book Speed Trap and reread it for the third time. Each of my three readings took place a decade apart (the book was published in 1992) and with each reading I had a different takeaway. This third reading reaffirmed many of my own conclusions in my own bio-motor specialty, strength. Charlie Francis bio-motor lane of expertise was speed. He developed a deep interest in strength because without strength, there is no speed. Strength bleeds over into speed.

Strength, and its subdivisions, absolute strength, explosive strength and sustained strength, is the undisputed King of bio-motor attributes. Ben Johnson, the world’s fastest human, could bench press 352 for ten reps weighing 180-pounds. This at the time of his 9.79 world record 100-meter dash run. He was not only the world’s fastest sprinter he also was the world’s strongest sprinter.

Charlie evolved his thinking about speed and speed training as he morphed from athlete (two-time Canadian 100-meter sprint champion) into a national and then international level coach. Francis was quizzing Iron Curtain sprint coaches in the 1970s on how they selected, constructed and trained their legion of world class sprinters.

Francis became an advocate of “less is better” and what I call “the rested effort.” To Francis' way of thinking, sprinters should run all out, 100% or more – but only when the runner was completely rested, recovered and “normalized.” Francis believed that the only way for sprinters to become faster was to run at 100% or more of their current capacity. The only way to improve top speed was to run at top speed.

Over time, by running at 100%, top end speed improved. To paraphrase him, how can we improve 100% speed unless we run, as often as possible at 100%? Running at 85% or 95% of capacity does not improve 100% capacity. The way to run faster is to run faster. Sub-maximal sprint efforts, repeated sprinting at less than capacity cannot and will not improve top-end speed.

Unless a sprinter is totally fresh, totally rested and totally free of any residual effects from previous training session, a 100% effort is impossible. Running all out without proper training recovery cannot and will not improve top end speed. After an all-out sprint session, all-out sprinting need be avoided until the body is fully recovered and fresh. Rested efforts require thought, attention and planning.

When in doubt, Francis had his sprinters sprint less. He would examine his sprinters as they warmed up, looking for telltale signs of fatigue, of being less than 100%. If he detected an uneven gait or heavy footfall, he would tell his sprinter to bag the all-out speed work, go hit the weight room, do some endurance work or go get a massage for maximum training recovery. No all-out sprinting unless the athlete is fresh.

Running all out, sprinting at 100% of capacity, stresses the body on every level and demands sufficient training recovery. Going as fast as humanly possible runs the risk of the body flying apart. The more his athletes engaged in true 100% work, the more resilient tendons, ligaments, muscles and facia became. His athletes were conditioned to withstand the centrifugal forces generated by running as fast as humanly possible.

Sprinter Ben Johnson hitting a bicep shot.

The parallels between Francis-style speed training and elite strength training are intriguing. The Francis approach could be described as a maximum intensity-minimum volume approach. the strength system we advocate is maximum intensity-minimum volume. He and I came to many of the same conclusions in two different arenas, pure speed and pure strength. To optimize strength-training workout performance, each session should be executed only after undergoing a full and complete training recovery from the previous high-intensity session.

- Less can be better if less is more intense

- Do fewer things better

- To improve strength or speed, equal or exceed (some expression of) 100%

- There are many different expressions of 100%

CNS/PNS: what Francis picked from his interactions with Iron Curtain sprint coaches was the idea that the CNS, the central nervous system needed to be fresh and rested for optimal sprinting.

- The central nervous system (CNS) consists of the brain and the spinal cord

- The peripheral nervous system (PNS) are the nerves and ganglia that stem from the CNS

“More recent research suggests Central Nervous System fatigue occurs to a greater extent with lower intensity, long duration exercise (moderate intensity/high volume.) If we don’t get some sort of acute CNS fatigue - should we really expect to get the neural adaptations normally associated with heavy resistance exercise? If a system isn’t stressed it will not adapt.”

Be it sprinting or power training, if the CNS is fried, fatigued, worn out, stressed out or burnt out, performance will be subpar. Fatigue inhibits the requisite electrical, neurological, chemical impulses needed to allow the runner to run all out or the lifter to lift all out. No one exceeds their personal best efforts when burnt out mentally or fatigued physically.

In order to run faster then we have ever run, to lift past capacity, the body’s muscular system and CNS/PNS need be stress-free and fresh. How does an athlete determine if the CNS is fresh and rested? Here are a few commonsense checklist items to determine if you are ready to train all out or if you need more time to “get back to zero”

- Mentally: Sharp? Fuzzy? Quick-witted? Distracted?

- How do you feel: Tired? Energetic? Fatigued? Vibrant?

- Outside factors: Home stress? Home bliss? Office stress? Upbeat and on a roll?

- Physiologically: Injuries? Injury free? Soreness? Zero soreness?

- Rest and training recovery: Adequate sleep? Lack of sleep? Sleep quality?

- Nutrition: on top of nutrition? ignoring nutrition? Well fed? Ill-fed?

Sprinter Ben Johnson In The Starting Blocks

Assess your condition upon awaking. If you are scheduled to train that day, rate how you feel on a 1-10 scale, 1 being “I feel terrible, sick and weak” and 10 being “I feel incredible!” A 7 means you feel average, not great, not bad, regular and ready to train. All through the day leading up to the training session, gauges your condition: how are you physiologically and psychologically on this day, at this exact time?

The training session should reflect the athlete’s state of preparedness. If you are not recovered from the previous high intensity lifting or sprinting session, delay the session 24-48 hours. What is the takeaway? Training recovery is more than muscular. An athlete can be physically ready yet if their CNS/PNS is burnt to a crisp, strength and speed will be subpar. There are innumerable ways to accelerate CNS/PNS recovery…

- Nutrition: quality calories heal and repair traumatized muscle tissue and cool down a jangly CNS/PNS. The nutrients need be nutrient-dense and plentiful. Empty calories are avoided.

- Supplementation: post-workout replenishment meals and shakes are a good idea assuming there is a skillful blending of high BV protein and glycogen-replacing carbohydrate.

- Hydrotherapy: whirlpool, steam, sauna and ice baths all have been shown to reduce pain, reduce swelling and inflammation, improve circulation and restore a shattered CNS.

- Mindfulness & Meditation: successful mental recalibration reduces stress, a major contributor to CNS fatigue. Faux meditative methods are superficial and a waste of time.

- Quality sleep & napping: there is a difference between deep sleep and restless sleep. Sleep plagued by thought is no sleep at all. Power naps are restorative if the sleep is deep.

General fitness: a fit athlete recovers better both on the muscular and CNS/PNS level. Cardio fitness paired with strength creates resiliency.

About the Author

As an athlete Marty Gallagher is a national and world champion in Olympic lifting and powerlifting. He was a world champion team coach in 1991 and coached Black's Gym to five national team titles. He's also coached some of the strongest men on the planet including Kirk Karwoski when he completed his world record 1,003 lb. squat. Today he teaches the US Secret Service and Tier 1 Spec Ops on how to maximize their strength in minimal time. As a writer since 1978 he’s written for Powerlifting USA, Milo, Flex Magazine, Muscle & Fitness, Prime Fitness, Washington Post, Dragon Door and now IRON COMPANY. He’s also the author of multiple books including Purposeful Primitive, Strong Medicine, Ed Coan’s book “Coan, The Man, the Myth, the Method" and numerous others. Read the Marty Gallagher biography here.