Speed and Strength: two sides of the same coin

Training to improve to maximum speed and training to improve absolute strength are remarkably similar

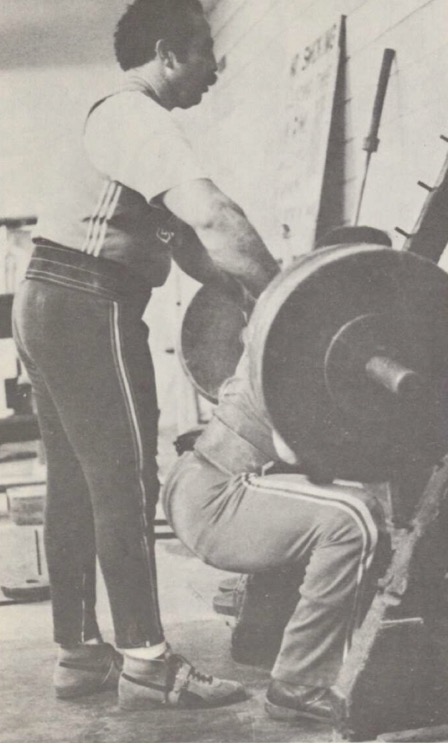

Power legend George Frenn (above) shows the proper way to one-man spot as Roger Estep reps 605 x 5

There are three generalized types of strength…

- Absolute strength: maximum payloads moved for low reps over short distances with no regard for velocity

- Explosive strength: moderate payloads moved for low reps using an extended range-of-motion and maximum velocity

- Sustained strength: light payloads and varying ranges-of-motion for extended periods using low velocity

The attainment of absolute strength and the attainment of top-end sprint speed are, philosophically, remarkably similar. Absolute strength cannot be improved using submaximal effort. All-out sprint speed cannot be increased with sub-maximal sprinting.

The body strengthens and builds itself in response to uber-intense past-capacity muscular and skeletal stresses. Only by generating herculean effort in our power training workouts are muscles forced to grow and strengthen. Less than maximum effort is insufficient to invoke hypertrophy or trigger strength increases.

Strength increases can only occur when the fully rested athlete handles poundage and reps that stress his body to its capacity, or optimally, past capacity, without injury. Sprinting all-out top speed increases can only occur when the fully rested sprinter runs as fast as humanly possible, up to and, optimally, past capacity, without injury. Here are three generalized rules that apply to powerlifting and sprinting…

- To increase strength or speed, generate a 100% + effort when 100% rested

- There is no point generating a 100% effort when 78% rested

- There is no point generating an 78% effort when 100% rested

Capacity and Strength Training

Capacity can be measured using many yardsticks. Capacity in power training is not about continually testing single-rep maximum lift strength. The commonsense definition for attaining 100% of capacity is as follows: pick any exercise, (preferably one of the Core Four or an acceptable variant) pick a technique, pick a poundage – now proceed to perform as many reps as possible. Rep until you cannot do another rep. You have just given 100%.

Optimally, the trainee periodically generates a 102% effort; a “past capacity” effort is achieved by adding a rep or two to an exercise set or by increasing poundage ever-so-slightly.

There are many expression of 100% capacity. Maximum capacity on any given day and time can be diminished, enhanced or unchanged. Capacity is a shifting target. Capacities are never static. Day to day, week to week, hour to hour, our 100% capacities (in the various exercises and drills, be it power training or sprinting) will rise, fall, or stay the same.

Capacity and Sprinting

The quest to improve all-out top speed has an amazing number of parallels to the quest to improve absolute strength. First and foremost: there is no speed without strength. Sprinting requires power and strength to propel body mass with optimal velocity. Weak runners might make fine distance runners, but they will never become more than mediocre sprinters. Strength can be acquired with proper strength training.

To improve all out top speed requires the athlete generate a 102% effort when 100% rested. Sound familiar? This identical mantra can be applied to strength training. Put differently, there can be no absolute strength gains, there can be no top end sprint speed gains, if the athlete lifts all-out or runs all-out in a fatigued state. No matter how well the lifter or sprinter performs during a partially recovered workout, the results derived from that same workout would have been improved had the athlete been fully recovered.

Commonalities

All-out power training sessions, and all-out sprint sessions need be infrequent. When fully recovered, engage in a high intensity workout, exerting maximally within the training session with repeated 100% efforts. Both sprint drills and powerlifting sets are short. Both seek to attain maximum exertion with a full tank of ATP, the body’s nitrous oxide. Nitrous provides hundreds of extra horsepower to racecar engines for a few brief seconds. ATP and a tank of nitrous both run out after about six seconds.

In an all-out speed session, in a limit-exceeding periodized power training session, the workout consists of a series of all-out efforts, with a goodly amount of rest between capacity equaling or capacity-exceeding efforts. Past a certain limited point in the training session, fatigue prevents further 100% efforts. Lifting all out, running all out, is counterproductive and potentially injurious if done while fatigued.

If there is a question in the athlete’s mind or coach’s mind as to if the sprinter or lifter is fully recovered – more time need be taken. When in doubt, kick the can down the road, delay the all-out session. Unless the athlete is 100% fresh, rested, alert and vital, training sessions will produce substandard results. The sprinter and strength athlete credo: train the body together, rest the body together.

All-out sprinting and heavy power training are inherently dangerous. When running all out, when sprinting as fast as humanly possible, your body is in danger of flying apart. You are one false step away from ripping, tearing, or pulling muscles. When you are attacking a limit 5-rep set in the squat, attempting to set a new personal record, pushing your guts out, you are one technical miscue away from ripping, tearing, or pulling muscles.

This element of danger concentrates the Mind. All out efforts require a melding of Mind and body to accomplish the past-capacity drill. A sloppy or inattentive athlete, running all out or lifting all out, put themselves in danger of catastrophic injury. Because of the relative simplicity of the task, the shortness of the sprint, the brevity of a powerlifting set, both lend themselves to intense psyche. The sprinter or powerlifter can take their psyche to the next level. A 100% physical effort is amplified and taken to 102% with the proper warrior psyche. Because the tasks are simple, all-out psyche is appropriate and advisable.

Speed and strength go together. They compliment one another. Ideally, the athlete practices both. Determine the optimal number of rest days you need between all-out lifting sessions. Determine the number of recovery days needed between all-out sprinting sessions. With proper recovery, workouts are never taken when fatigued. Train the body together, rest the body together. Learn to exert 100% safely and consistently, this is where the physical gains lie hidden in plain sight.