The Case For Absolute Strength

Déjà vu all over again

Athletic men that lift weights using absolute strength techniques and tactics become larger, more powerful versions of their athletic selves. Unathletic men that lift weights using absolute strength techniques and tactics become larger, more powerful versions of their unathletic selves.

I got into a philosophic tiff the other day with a fight trainer (a good one) that told me his stable of fighters “did not need absolute strength – that’s not the type of strength fighters want or need.” Fighters, he continued, need “strength endurance” and all his strength training efforts were confined to “drills that created sustained strength, the kind of strength that can be called upon deep into the third, 5-minute round of an MMA fight.”

The MMA coach had his fighters push wheelbarrows loaded with barbell plates up steep grades, throw medicine balls for height and distance, pick each other up and run around the circumference of the gym, shoulder a 100-pound heavy bags and start doing repetitions in the Supplex, sprint up steep hills wearing weight vests, etc.

All his drills were designed to build a fighter’s “gas tank,” the fighter’s ability to endure and “put out” deep into a fight. His final stinging retort, “We don’t need to build a fighter’s bench press.” First off, I love his strength endurance drills and want him to keep them up. But this is not an either/or deal, a choice between strength-endurance and absolute strength. All athletes, including fighters, need strength-endurance and absolute strength. Not one or the other, both.

His dismissal of the need for absolute strength is one I have heard for decades. It sounded so déjà vu, so familiar. His attitude exactly reflected the attitudes of olden day football coaches, lockstep thinking men of the 1950s and 1960s who forbade players from weight training because weight training would slow them down, make them musclebound, and ruin their athletic ability.

This was settled science: coaches revoked the scholarships of Division I players caught secretly lifting weights. So, what changed this attitude? When did the seismic shift occur – from an era when lifters were forbidden to lift weights to an era where all college and pro players were required to lift weights?

Football coaches got their minds changed for them. They were bitch-slapped into reality when their non-weight trained players started getting manhandled, overwhelmed, overpowered, tossed aside, pancaked, position by position, by a new breed of way bigger, way stronger, just as fast, just as agile, weight-trained players.

The emergence of the powerhouse weight-trained Pittsburg Steelers in the 1970s was the game changer in pro football. Head coach Chuck Noll was a weight trainer himself and brought in world record holder (325 snatch, 181-pound class) Lou Rieke to become the NFLs second fulltime strength coach. Alvin Roy of the San Diego Chargers, under head coach Sid Gillman, was the first.

Lou was old school all the way. The mighty Steelers weight trained in the basement of a bar (how fitting and convenient!) At the time NFL teams did not have onsite weight training facilities. Lou had these future hall-of-fame players squat (lots!) power clean, bench press, overhead press, deadlift, row, and work arms at the end of every session. Then they would go upstairs and drink beer by the pitcher.

Both on offense and defense the Steelers beat the hell out of every other NFL team. (except mighty Oakland) The Steelers were just as fast, just as agile, they had just as much endurance as any other team - but they were way bigger and way stronger.

Until the emergence of the Steelers, defensive tackles in the NFL were averaging 260-pounds and defensive ends 240. The Steelers put an end to small ball: all pro center Mike Webster weighed 275 pounds with a 10% body fat percentile. He was squatting 700 + for reps, bench pressing 500 + for reps and his cardio was so good that he was the only member of the squad that could run up and down every step in Three River Stadium without stopping. He decimated opponents.

Webster used absolute strength training to create an amplified version of Mike Webster without absolute strength training.

Someone else that did that was the immortal Walter Payton. When Walter came out of Mississippi Valley State, he weighed 185-pounds and was a low draft pick. He added 20-pounds of lean, weight-trained muscle and at 205-pounds became a power runner and a demi-god. Football coaches changed their tune when their teams started getting beaten up and embarrassed by muscled-up opponents.

Once upon a time, Olympic weightlifters did the three competitive lifts exclusively: the press, snatch, clean and jerk. These lifter of the 1940s and 1950s eschewed squats and deadlifts, stating that they did not need “that kind of strength.”

Absolute strength training would slow them down, destroy the lightning-fast reflexes needed for optimal Olympic weightlifting. Doing other lifts would take away time that could and should be dedicated towards getting ever more technically proficient at the three lifts.

That was settled science. When did the seismic shift occur – from an era when Olympic weightlifters were forbidden to do any lift other than the press, snatch or clean and jerk (or some variation) to an era when all Olympic weightlifters were required to use other lifts to improve performance in the three competitive lifts?

The mind-changer in this case was a massive, unnaturally strong hillbilly named Paul Anderson. At age 22 weighing 340-pounds, Paul was stupid strong. He overpowered and bulled up poundage, technique be damned. On Anderson’s first trip to the Soviet Union in 1955 he made mincemeat of the Soviet world and Olympic champion.

Nominally, world records are moved upward in 2.5 kilo (5.5 pounds) bumps, Anderson, in one fell swoop moved the world record in the overhead press upwards from 363 to 402, this in Gorky Park, Moscow, in the rain, in front of 5,000 mind-blown, gob smacked Russians. For some inherent reason, Russians love chess and Olympic weightlifting.

During his extended State Department-sponsored visit, Anderson requested his Russian hosts construct for him a set of squat racks. After seeing Paul squat 700 for reps, and then seeing Anderson crush the best lifters in the world, a light bulb went off. On Anderson’s next trip to Russia there were squat racks galore. The Russians had adopted squatting as a regular part of their training template.

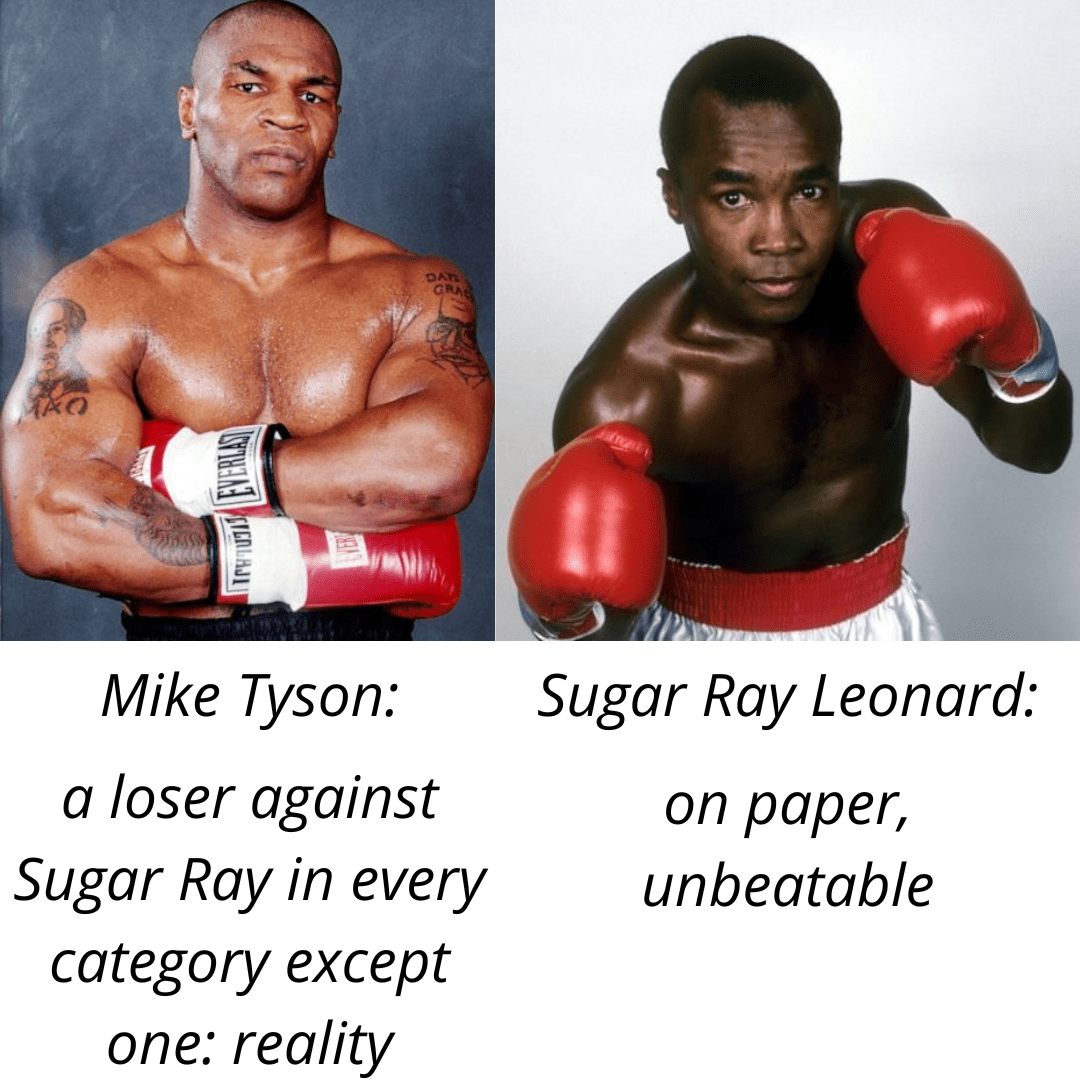

I mentioned to my fight trainer friend that Sugar Ray Leonard was one-half inch taller than Mike Tyson: Ray was 5-10.5 while Tyson was 5-10. I asked my MMA fight coach friend, the man that dismissed the need for absolute strength, who would win if Ray and Tyson fought at their respective peak, “Tyson of course.” Yet, on paper, Ray trumps Tyson in every category – save one.

Ray Leonard Mike Tyson

- Speed +

- Agility +

- Flexibility +

- Endurance +

- Reaction time +

- Fight skills +

- Experience +

- Titles +

- Ring savvy +

- Power, size, strength +

Tyson at his peak weighed 218 pounds, Ray was 156, a 62-pound weight differential

My counterargument was simple: if size, power, and strength did not matter, if absolute strength did not matter, then why does MMA have weight classes? It was a rhetorical question: they need weight classes because dramatic inequalities in size and strength (amongst equals) cannot be overcome. As the old boxing cliché goes, “A good big whips a good little man every time.”

The maddening part for me is that absolute strength can be accomplished by allotting a mere one hour per week. Cutting-edge strength minimalists that we are, our approach is to have the trained fighter squat, bench press, deadlift, and overhead press, once a week, all in the same session. Work up to a single “top set” using whatever poundage and rep scheme the periodized (preplanned) schedule called for. Then move onto the next exercise. Absolute strength can be improved 40% with 12-weeks of application. That is a lot of return for a one-hour weekly time investment.

Power train for an hour per week with all your heart – then go do what you do.

Keep pursuing sustained strength, build that bigger gas tank, keep doing all your current fighter drills and protocols; just give me one hour a week to power-ize your athletes. I will hand you back fighters way stronger and yet just as lean, just as fast, just as agile. Factually, they will be faster after working with me: absolute-style weight training makes all athletes faster. The world’s greatest sprinters all engage in hardcore weight training and have done so since the 1960s.

Power-trained fighters develop a vastly improved resistance to injury. This is one of the underreported benefits of power training; hard, heavy, consistent lifting thickens and strengthens tendons and ligaments at muscle insertion points. Dramatic strength increases make any contact athlete more durable and blow resistant. We know this from our work with football and rugby players. Heavy lifting makes any athlete sturdier and far less susceptible to training mishaps and minor nagging injuries that can derail a fighter’s career.

Stronger fighters hit way harder and kick a hell of a lot harder. Stronger fighters overwhelm weaker opponents in clinches and scrambles. All this for an hour a week? Some attitudes never die. This MMA coach is the modern reincarnation of the 1960s football coach. Will my MMA coach buddy be swayed by my irrefutable logic? I doubt it. As my Irish dad used to say, “A man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still.” I suspect the only thing that will sway his rigid mindset is when a bunch of muscled-up ape fighters begin overwhelming his super-fit skinny boys.

About the Author - Marty Gallagher

As an athlete Marty Gallagher is a national and world champion in Olympic lifting and powerlifting. He was a world champion team coach in 1991 and coached Black's Gym to five national team titles. He's also coached some of the strongest men on the planet including Kirk Karwoski when he completed his world record 1,003 lb. squat. Today he teaches the US Secret Service and Tier 1 Spec Ops on how to maximize their strength in minimal time. As a writer since 1978 he’s written for Powerlifting USA, Milo, Flex Magazine, Muscle & Fitness, Prime Fitness, Washington Post, Dragon Door and now IRON COMPANY. He’s also the author of multiple books including Purposeful Primitive, Strong Medicine, Ed Coan’s book “Coan, The Man, the Myth, the Method" and numerous others. Read the Marty Gallagher Biography for a more in depth look at his credentials as an athlete, coach and writer.