Dorian Yates - Forged Passion

Dr. Jim Wright contacted me about coming to work for the Weider organization in the late 1980s. During my tenure I wrote 84 feature articles for Muscle & Fitness, Prime and Flex Magazine. I was flown to the Mr. Olympia and the Arnold Classic and sat in the front row to write about the shows, interview the winners and roam backstage gathering impressions. All of which was rather odd for a man that really didn’t like bodybuilding. You don’t have to be a great artist to be a great art critic and you don’t have to be a bodybuilder to write insightful pieces on bodybuilding and bodybuilders.

My main area of expertise was training. I was also a realwriter with passion and a voice and I knew training backwards and forwards. I became the go-to guy who wrote the bodybuilding training/nutrition articles for M&F when the Weider empire was at its peak. The internet had not yet arrived to destroy the magazine business and M&F was the biggest bodybuilding publication in the world. At the corporate peak, Joe (Weider) maintained a “stable” of contract “athletes.” The numbers shifted year to year, but Joe usually had thirty to forty male bodybuilders and perhaps ten women under contract.

Winning a Weider contract was a big deal, akin to obtaining a bodybuilding scholarship. The contract size varied, but most times it allowed the bodybuilder to quit working a regular day job and dedicate 100% of their time and effort into becoming the best possible IFBB pro bodybuilder they could become. The competition was fierce for these slots and Joe would pull a contract from an old pro and reassign it to an up-and-comer in a heartbeat. The top slot and biggest paycheck was reserved for winning the Olympia, bodybuilding’s premier event.

A lot of my job consisted of writing feature articles on the star bodybuilders under contract. The articles were always accompanied by photos shot by the best physique photographers in the world, guys like Chris Lund and Ralph Dehaan. I got the job because Jim and Julian (Schmidt) had been fans of my gonzo strength articles written for Powerlifting USA and MILO, a strength journal.

I had followed bodybuilding for decades. As an Olympic lifter and powerlifter, our sports always shared magazine space with bodybuilding. It was an uneasy alliance as the athletic lifters had a lot of distain for these strange ‘mirror athletes.’ Bodybuilders sought to perfect form without regard to function. There were a rare few elite bodybuilders that were athletic and strong. These strong, functional bodybuilders developed thick, dense muscle mass. They looked power-packed; they had big-ass legs, bulging traps and thick back muscles. That was the type of body I envied and coveted as an aspiring preteen and teen lifter.

These men looked strong because they were strong: John Grimek (the world’s best built man for a decade) made the 1936 Olympic weightlifting team, he cleaned and strict pressed 285-pounds weighing 180; Reg Park pressed 300-pounds in the seated behind-the-neck press and could strict curl 185; Marvin Eder was the first sub 200-pound man to bench press 500-pounds; Bill Pearl squatted 600-pounds, raw, weighing 250 at an exhibition; Arnold won the Austrian powerlifting championships; Franco deadlifted 700 and benched 525 weighing 185; Sergio Oliva was on the Cuban national weightlifting team. This thick-muscled look that accompanied real power was dubbed, “the power physique.”

Bodybuilding judging standards shifted dramatically in the mid-1970s. Suddenly size was passé and penalized. Lithe slimness became the new judging ideal. It was dark times for bodybuilding as small men with tiny bone structures and low body fat percentiles began winning Olympias. How in the hell could any sane bodybuilding judge say that Frank Zane’s tiny body was superior to the incredible Robbie Robinson, a man that Zane inexplicably beat twice! Once in 1977 and again at the 1978 Olympia. Insane. How does a man with 16.5-inch arms win the Olympia? As Chris Dickerson did in 1982, beating a ripped to the bone, 245-pound man with 21-inch arms, Bertil Fox.

Some sanity was restored with the long reign of Lee Haney. While he ruled long and was dominate, it was generally considered a period of bodybuilding stagnation. Things became interesting with Haney’s retirement in 1991. Dorian Yates, a European mystery man, had come out of nowhere to shag a distant second place to the outgoing champion at the 1991 Mr. Olympia. This was an omen of things to come.

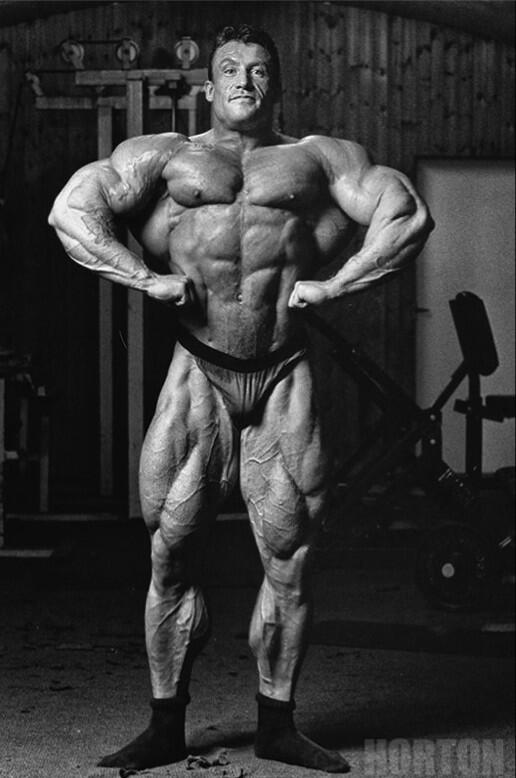

The tattooed Englishman had been decimating the European competition yet was completely unknown in America. Yates stood a solid 5-foot 10-inches in height and competed at a ripped 225, not just ripped “absolutely shredded,” was the word from Europe. He announced his arrival internationally with his surprise second place finish at the Olympia. Yates had a look about him that reeked tough guy.

Not surprisingly, I later found out he learned lifting in reform school. So his was not a feigned or faux toughness. When I saw his first photos I noted that all his poses were aggressive and arrogant; yet he seemed man enough to pull it off. My first impressions were that he had incredible calves, a great back and a cool haircut.

I thought he’d do quite well against the current crop of IFBB pros; though no way did I think that within a year he would become the dominant bodybuilder in the world. Size-wise, he was no bigger than the rest of the top pros already on the scene. The American pros were dismissive of early Dorian. His second place to Lee was regarded as a weird fluke. Yes, he had amazing condition for a 225-pound guy, but, so what the detractors said, look at his wide hips and the fact that he did not have ‘pro arms.’ Another pro told me, “He seems awkward when posing…no flow, no grace.”

At the 1992 Mr. Olympia American dark horse newcomer Kevin Lavrone, an unheard-of Maryland bodybuilder (and good friend of my Maryland-based power protégé Kirk Karwoski) took second place to Dorian Yates at the Helsinki Olympia. This was the beginning of Yates’ six-year reign. Yates weighed 228. In the off season, after his Olympia win, Yates used power training and an increase in clean calories to push his bodyweight up to a staggering 290 pounds, this while maintaining a 10% body fat percentile.

Dorian then trimmed back to 270-pounds and had a series of photos shot in his subterranean, dank, dungeon-like Temple Street Gym. These were stark, bleak, black and white photos shot in bleak Birmingham, England. It was a series of dead-simple, black-and-white mandatory poses. Yates revealed his new 270-pound body and sent shock waves through the bodybuilding world. It was as if the 225-pound Yates had swallowed an air hose. He looked photo-shopped before there was photo-shop. The degree of improvement in such a short timeframe was unprecedented.

Because he had maintained his outstanding degree of condition, Dorian Yate was a very scary opponent. For some reason, someone stuck Dorian with the moniker, “The Shadow.” I never saw anything remotely shadowy about Yates. I would have recommended, “The Nightmare.” Much later he finally got the street name I thought he deserved, The Diesel.

Yates now combined Platz-like legs with the best back in the history of bodybuilding. Plus he became the first giant guy in history to figure out how to get little-man ripped. It was mind-blowing. The question on every pros lips was, how does a top pro, a man already at the top of his game, how does this man find a way to add forty pounds of ripped muscle?

Truthfully, Yates was unnaturally drawn winning his first Olympia weighing 228. He could have easily have weighed 240 that night, with no loss in condition. His off-season weight had been 260 while staying at 10%. After blowing up to 290, Dorian dieted down for the 1993 Olympia. The greatest Dorian of all time walked onstage that night weighing 257-pounds with likely a 4% body fat percentile. The 1993 Mr. Olympia would be his peak year. He crushed the best in the world while stifling a yawn.

In 1994 Yates was on track to take the next level to the next level. He pushed his off-season bodyweight up to a biscuit shy of 300-pounds. He was handling gargantuan training poundage in core barbell and dumbbell exercises and was having the best training sessions of his career. In 1994 Dorian suffered a serious shoulder injury that would require surgery. Soon after he tore a vastus muscle in his left thigh so severely that he was unable to do any leg training. The final blow occurred when he tore his left bicep and was not able to have it reattached. This created a flaw in the Yates’ physique. All this in 1994 coming off his greatest win. All told, he won six straight Olympia titles.

Dorian had no real mentors to speak of. He pledged allegiance to Mike Mentzer’s Heavy Duty less-is-better training protocols; but it wasn’t as if the two men trained together. I examined Yates’ training in depth and at length, and, to me, his approach was not Mentzer or Jones’ one-set-to-failure-plus forced reps and negatives. This was something entirely different. He had created a unique hybrid system I called power-bodybuilding. He got way bigger because he found a way to get way stronger.

Dorian just didn’t walk in, sit down on the 45-degree incline bench and start repping 435-pounds for 6-reps before Leroi would step in and assist in two more forced reps. Dorian needed to warm-up with 135 for 8, then 225 for 5, 315 for 5 and 365 for 1 before finally tying into 435 for 6 + 2 forced. Ditto all the other exercises, he needed warmup sets. Yates handled 450-pounds for reps in the row, 1200-pounds in his leg presses and did 500-pound hack squats. You got to warm-up before attacking that kind of poundage.

This could hardly be called one set to failure plus force reps: call it honestly, i.e. a lot of warm-up sets before one set to failure + some forced reps or drop sets. To my expert way of thinking, Yate’s approach was powerlifting with forced reps and drop sets. He used an expanded training menu. Yates trained a muscle once a week, just like an elite powerlifter and would work up to one all out top set. His ferocious training partner would add a few forced reps. He would then move on to the next exercise. Four weekly sessions took about one hour to complete. Heavy and plain, was how I described it in an M&F back training article I did with him after he won in 1996.

I penned another article in Muscle & Fitness talking about the similarities between Dorian’s training split and powerlifting immortal Ed Coan’s training template. I opined that Dorian’s training was that of a bodybuilder using powerlifting strategies while Ed was a powerlifter augmenting with a lot of bodybuilding exercises. Each man used incredible poundage in a wide variety of exercises. There were far more similarities than differences in the two men’s training templates. At one glorious time, the world’s best built man and the world’s strongest man trained essentially the same, alike in more ways than not.

J.P. Brice would likely point to Dorian’s many Olympia wins after the 1994 training injuries as indicators of Yates’ “forged passion.” Dorian had strength of character and an indomitable mindset. He had an ability to comeback in the face of not one, not two, but three serious, career-ending injuries. It was all indicative of iron determination. Yates always won. His rugged personality and unpretentious stance mirrored his rugged physique. At his peak he simply dominated: he presented an Ice God physique that stills resonates with the youth of today. Bodybuilding may be form without function however Yates at his awesome peak reeked of function taken herculean form.

About the Author

As an athlete Marty Gallagher is a national and world champion in Olympic lifting and powerlifting. He was a world champion team coach in 1991 and coached Black's Gym to five national team titles. He's also coached some of the strongest men on the planet including Kirk Karwoski when he completed his world record 1,003 lb. squat. Today he teaches the US Secret Service and Tier 1 Spec Ops on how to maximize their strength in minimal time. As a writer since 1978 he’s written for Powerlifting USA, Milo, Flex Magazine, Muscle & Fitness, Prime Fitness, Washington Post, Dragon Door and now IRON COMPANY. He’s also the author of numerous books including Purposeful Primitive, Strong Medicine, Ed Coan’s book “Coan, The Man, the Myth, the Method" and numerous others. Read the Marty Gallagher biography here.